Natural Gas Datacenter Makes Home on the Range

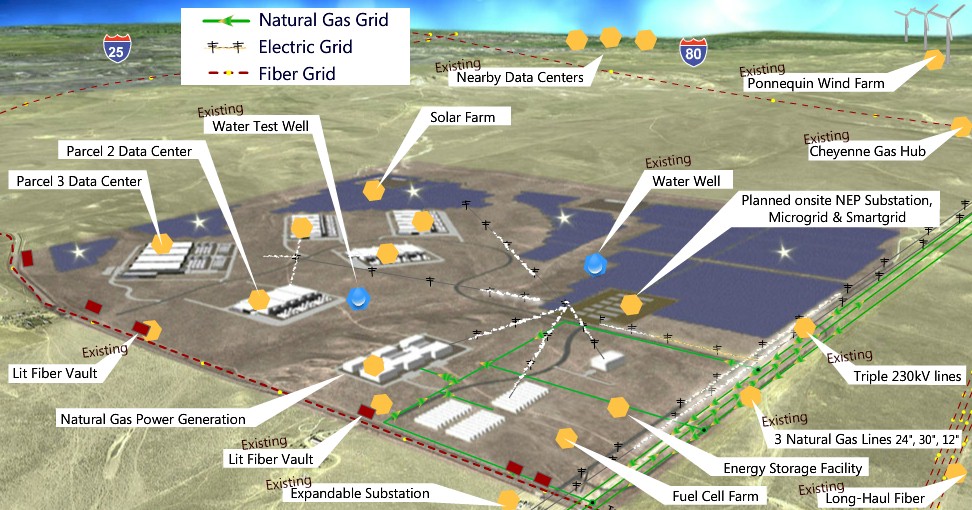

After three years of land acquisitions, zoning applications, and the attainment of a license to generate its own electricity from the local natural gas supply, the Niobrara Data Center Energy Park located in northern Colorado has everything in place to attract a truly massive datacenter. And it will very likely do so soon because of the reliability and low-cost of natural gas supplies in the region.

The datacenter site is unique in a number of ways, Craig Harrison, creator of the park, explained to EnterpriseTech. Harrison is also general manager of Niobrara NatGas, the natural gas utility that has just been licensed to operate on the site on behalf of potential datacenter customers who decide to buy or lease the 662-acre facility. Harrison is quite proud of the fact that this is the first new gas utility to be licensed in the state of Colorado in the past 15 years, and once this feat was accomplished, Niobrara is now looking for tenants.

The Niobrara site is a nexus of just about every kind of useful infrastructure, geology, and weather that a data center would require. It has plenty of local water for cooling (135 million gallons per year can be drawn out of the ground) as well as lots of sunshine to be caught by solar arrays if a datacenter operator wants to use a mix of natural gas and solar cells to provide electricity for their facilities. The climate is temperate enough for outside air cooling and the air is dry enough to not cause humidity problems in the datacenter. Facebook's first datacenter in Prineville, Oregon uses outside air and actually had clouds forming in the facility.

Niobrara is not the first company to find the corridor between Denver and Cheyenne, Wyoming attractive for datacenters. The 1.5 petaflops "Yellowstone" supercomputer built by IBM for the National Center for Atmospheric Research is located west of Cheyenne and uses outside air cooling. And about 15 miles up the road from the Niobrara site, to the south of Cheyenne, Microsoft also has what is believed to be a chillerless datacenter, too.

Harrison says that it will cost on the order of $4 billion to fully develop the Niobrara park, which he called a "digital Fort Knox" because of the energy security it has. While the site does not generate its own natural gas, it is situated 3,600 feet from three natural gas lines that provide 1.5 billion cubic feet of gas per day. The site is zoned to have as much as 50 megawatts of electric generating capacity from Bloom Energy's fuel cells. These fuel cells, which convert natural gas to electricity using a super-secret process, are also powering up the new eBay datacenter outside of Salt Lake City, Utah.

The site is also zoned to have a 200 megawatt generating plant comprised of an array of 9.3 megawatt Wartsila reciprocating engine generators and a microgrid to distribute that power. By using these Wartsila generators, the datacenter that takes over the Niobrara site will be able to ramp up their power generation in lockstep with the datacenter build out.

"The natural gas supply is so safe and secure that you can build a datacenter without backup diesel generators or uninterruptible power supplies," says Harrison.

Harrison has teamed up with CH2M Hill to do the engineering work for the Niobrara site, and with the combination of natural gas generation and the elimination of generators and UPSes as well as chillers for cooling the datacenters, the fully scaled up site would cost $800 million less to build than a conventional chilled datacenter running off the electric power grid. And the operational savings would be on the order of 50 percent lower, he says, because of the efficiency of generating the electricity right on site using natural gas, which is abundant and relatively cheap.

If a datacenter operator doesn't want to trust the gas grid and local electricity generation, the site has space for 200 acres of solar arrays, which can generate something on the order of 25 to 30 megawatts of juice. And there is another 100 megawatts of connectivity coming in from the local power grid, too. Any datacenter operator on this site will need to connect to the outside electric grid no matter what. The gas-fired generators have to create more electricity than the datacenter (or datacenters) will use at any given time. You always want to generate more power than you need, not less. And any excess has to be pumped into the public grid.

For connectivity, the Niobrara site is only a few miles from the main fiber trunks that come out of Denver heading north owned by CenturyLink, Level 3, AT&T, Zayo, and Sprint, and the site already has six active fiber vaults along the south end of the property that provide connectivity out to these trunks. The average latency from Weld County, Colorado, to major cities in the United States is on the order of 31.5 milliseconds, which is lower than the national average of 37.2 milliseconds and a lot lower than the 55.8 milliseconds from Facebook's Prineville, Oregon data center or Microsoft's Quincy, Washington datacenters, which are at 55.8 milliseconds.

To fully develop the site, Harrison expects it would cost $1 billion to develop the datacenters, plus another $700 million for the gas plants, microgrid, and fuel cells. Filling up the datacenters with servers, storage, and networking gear would be the biggest chunk of the cost, at around $2.5 billion. All told, the site could have something on the order of 1.5 million square feet of total building space with 200 megawatts of power.

This is a truly monster site – and one that Harrison expects to only stay vacant for about six months. Because large enterprises or government agencies don't like to share datacenter sites, it seems likely that a big hyperscale datacenter operator will snap it up.

Niobrara also has a killer view of the Rockies, of course. Not that this matters to the servers.