Intel Uses Moore’s Law And Virtualization To Shrink Its Datacenters

Chip maker Intel operates one of the largest clusters in the world to push Moore’s Law along with its electronic design automation systems, as EnterpriseTech has previously revealed. But the $53 billion company is also a one of the largest manufacturers in the world. As such, it faces the same challenges in the datacenter as other manufacturers of the same size and scope. Like its peers, Intel has to carefully plan all of its expenditures because manufacturing is such a capital intensive business. This is as true for the many thousands of servers that are used to run the business as it is for a chip factory or a design cluster.

It takes a lot of iron to run Intel. Not only does the company need hefty back office systems to do the books and run its supply chain and distribution operations, but with 105,000 employees worldwide, providing applications and collaboration tools for those workers also takes a lot of iron. When Diane Bryant, who runs Intel’s Data Center and Connected Systems Group today was the firm’s CIO a few years back, one of the first things she did was do a server survey. And in doing so, Intel found thousands of old servers that were not doing anything useful and got rid of them.

The second thing Bryant did was initiate an effort to get as many of the workloads running on Intel’s corporate systems virtualized. (It makes little sense to virtualize the EDA clusters because of the performance overhead virtualization imposes.) Inside Intel, these are known as the Office, Enterprise, and Services systems, and they are located in eight datacenters around the world.

“We try to operating OES as efficiently as possible, and we are moving it to a cloud environment,” David Aires, general manager of Intel’s global IT operations and services, tells EnterpriseTech. “We have been on this journey for the past four years. The first step was to virtualize the environment, and today we are like 85 percent virtualized. Then the next step is to start transitioning to a cloud model, and then to ultimately get to a hybrid cloud. We are targeting to go to an OpenStack framework.”

Intel doesn’t talk about who its server and operating system suppliers are, and it doesn’t talk about which hypervisors it uses for its corporate systems, either. (To do so looks like an endorsement, something all Global 2000 companies seek to avoid doing.) Intel won’t be specific about what its server spending is, except to say that it is several tens of millions of dollars per year. And it will talk in detail about how it has made progress in virtualizing its systems and what virtualization has done for its budget.

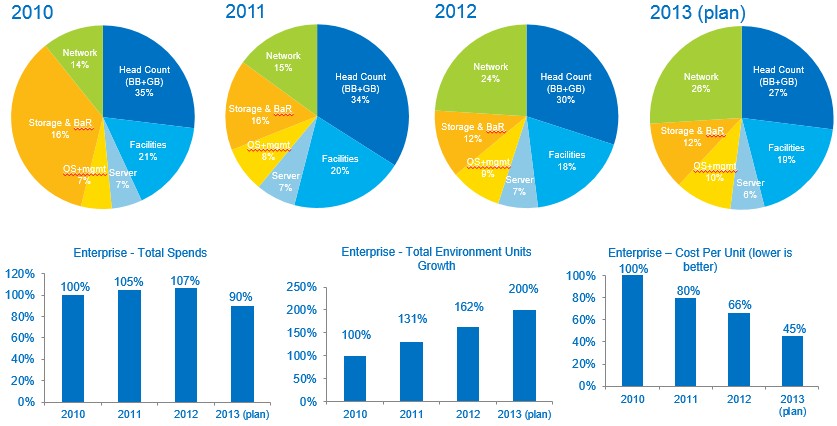

Here is how the budget for the OES systems stacked up for the past four years, with estimates for 2013 because Intel was not yet done with last year when this presentation was put together:

As you can see, Intel had a hard time keeping its IT budget from growing from 2010 through 2012 as it was changing a lot of aspects of its OES systems over that time. But, if you look at the number of operating system instances that the company supported over that time – what it calls total environment units – then you can see that even as the budget was wiggling up and down, the number of environments supported doubled in those four years and the cost per environment was cut by more than half. Aires says that Intel does exhaustive comparisons of its cist per virtual and physical machine in the OES datacenters, and that Intel is able to run its machines at a lower cost than public clouds. Once again demonstrating that at a certain scale, it makes more sense to run your own datacenter than to farm it out. In Intel’s case, the difference in costs is on the order of 10 percent or so, depending on the year, and this is enough to make it worth the company’s while. Also, when you make server components aimed at enterprises for a living, it probably makes sense to actually run them yourself to get instant and immediate feedback.

One of the ways that Intel has cut costs in the OES datacenters is by shifting from rack servers and external top-of-rack switches to converged systems, which integrate servers, storage, and networking. The cost for a virtual machine on a converged system using 10 Gb/sec Ethernet links on the server nodes today is about 40 percent lower than the cost of as rack-mounted server and 1 Gb/sec Ethernet ports and outboard switches. (Those comparisons also include Fibre Channel switches to link servers to storage arrays.)

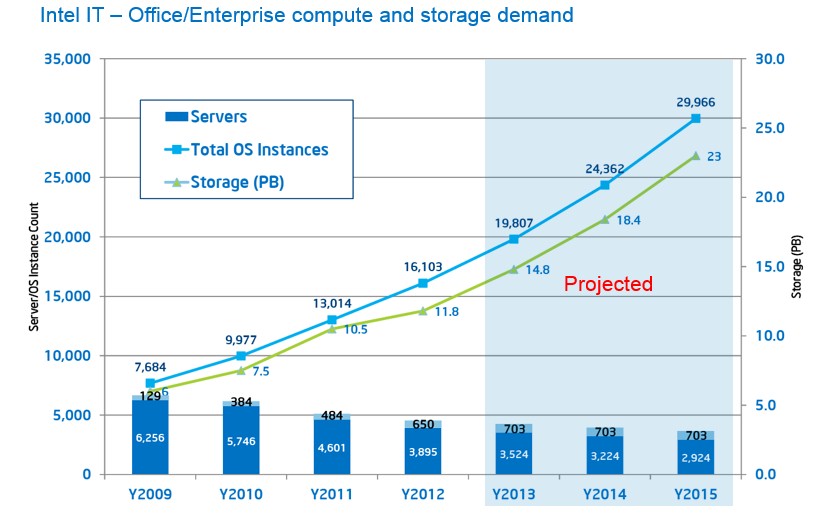

Now, here is the amazing thing: while 85 percent of the operating system environments at Intel have been virtualized, the vast majority of servers at Intel remain unvirtualized – and very likely will remain so for many years to come. Take a look:

Here’s how this chart works. In 2009, Intel had 6,256 physical servers in the OES organization, and a mere 129 servers were equipped with hypervisors to create virtual 1,428 virtual operating system instances. That is a total of 7,684 operating systems, or an average of about 11 instances per server that has been virtualized. Hypervisors had been around since the early 2000s for servers, and Intel was just getting going in 2009, concurrent with the launch of its own “Nehalem-EP” Xeon 5500 processors, which had the processing and memory capacity as well as virtualization assistance features to help hypervisors run more efficiently.

As you can see, over time Intel has reduced the number of physical servers in the OES fleet while at the same time increasing the number of virtualized machines and the number of VMs per machine on those latter boxes. As 2013 was coming to a close, Intel was projecting that it would have 16,283 virtualized operating system instances running on 703 servers, or an average of 23 VMs per machine. The number of strictly physical servers has dropped by 44 percent to 3,524 over the same time. Looking out into 2014 and 2015, the charts show the number of virtualized servers staying constant and the number of physical servers continuing to drop, but Aires tells EnterpriseTech that Intel wants to leverage Moore’s Law and the growing number of cores per chip to push that server count down faster for its virtual fleet.

“When we deploy Xeon machines with 10, 12. Or 15 cores per processor, even though demand for total OS instances goes up 20 to 30 percent, we will be able to meet the OS instance growth,” says Aires. “We are expecting somewhere between 50 and 70 OS instances to be hosted on every physical server when we refresh.”

Aires says that the most constrained resource on its virtualized systems is not CPU cores or utilization, but memory. “The memory utilization is around 51 percent, but the CPU is running at around 21 percent,” Aires explains. “We are still not very efficient at running these virtualized servers.”

But Intel is committed to making it better – and for its own good as well as for that of the tens of millions of customers who use systems based on its Xeon processors worldwide to run their businesses.